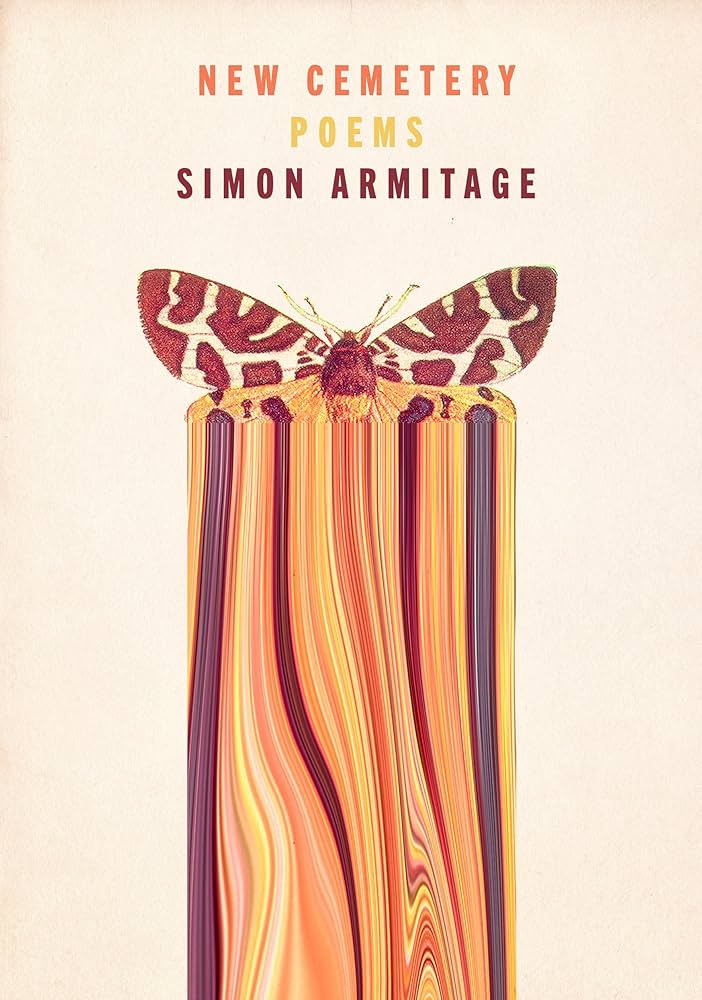

A school of fish, a swarm of bees, a murder of crows – most animals only get one, but moths boast two collective nouns: an eclipse and a whisper. In New Cemetery, the latest collection of poems from Simon Armitage, a whispering eclipse of tercets takes wing on every page. In a poem titled “Speckled Yellow” (after the moth species that looks that way) the poet addresses the cosmos.

Dear universe, I shaved this morning – look at these fine black pinpricks constellated in the white sink. The new moon of this nail clipping proves I’m alive, and once every couple of months I regrow a fringe. Universe, it’s against you I measure myself: the laws of thermodynamics are calling my warm atoms into deep space, but for now I’m holding this hair, these bristles, this middle finger up to your smug face.

Falling somewhere sanely between Virginia Woolf and, say, Nabokov, Armitage seems more than merely enraptured with the literary potential of Lepidoptera (though what poet could resist, on a purely linguistic level, the fragile allure of the Dark Brocade, the Blossom Underwing, or the May Highflyer?). No, Armitage seems concerned with their ongoing existence.

Moths, the poet announces in his preface (itself titled “Moths”) – moths aren’t doing great. “Gone are the days,” he writes, “when the windscreen would be smeared with a gluey porridge of splattered bugs after a drive through a summer night.” Their populations, he reports, are in decline. So if the real thing is growing rarer, why not make moths out of words? And tercets: Every poem offers, in measured repetition, the ideogram of a line-slim body flanked by line-thin wings, the titles themselves finding all manner of serendipitous resonance (though Armitage assigned them, apparently, at random) with their contents (such as the alliterative mirroring of the phrase “printed page” in the poem “Pauper Pug”).

Don’t be fooled, though: the insects are something of a distraction. The book takes its title and spirals out from the construction of a new cemetery in Huddersfield, the West Yorkshire town that Armitage (Britain’s sitting Poet Laureate) calls home. Of whom it would be fair to expect something on the order of sanctimoniousness, given such a stark contrast between the size of the fish and that of the pond, but there isn’t a hint of holier-than-thou in evidence – nothing new, it must be said, for the poet who has always seemed just as comfortably couched in the argot of Oxford as the patois of pubs and phonebooks.

All of which has made for a bracingly intelligent, profoundly local kind of book. Documenting everything from the “bulldozers / peeling back turf” to an afternoon cloud the shape of a “retired Olympian / stealing his sister’s purse,” the poet’s role in the course of his hundred pages is to occupy a position not so much of authority or of power as of hard-won jurisdiction. More Gilbert-White-in-Selborne than busy-body-binocular-fumbler, the book’s best poems sound the kind of perfectly domestic note that can’t be faked by transplants, as in “Rannoch Sprawler,” which opens with a “Site inspection / and weather report: light snow / fringing cemetery lanes, // old ice / lending all graves / a pewter-cum-frosted glass- // cum-marquisette frame.”

And then there’s the humor, that unmistakable wit that is part and parcel of Armitage’s trademark self-deprecation. In “Chevron,” as elsewhere, he addresses the poem to the present reader.

Dear reader,

this evening the poet

has gone to his shed,

to temper his thoughts

in the prayer-shaped furnace

of a candle’s flame,

to throw with his hand

wild shadow puppets

onto the starched page. So what

if there’s nothing to say:

this poem, born to itself,

for its own sake.

In New Cemetery, Armitage proves yet again that he can do it all. Here, in epigrams and back-of-the-napkin narratives, in brief appreciations that approximate gratitude lists in their childlike reverence and songs in their musicality, he hasn’t written a poem that wouldn’t fit on one side of a standard tombstone. Literary smallness is in, and everyone is downsizing. But for Armitage the move toward brevity is a call to compression, a contest of nuance and efficiency, the same trial that any poet worth his salt has ever taken seriously – that of saying more with less. As this book so amply demonstrates, he remains one of his artform’s most ingenious practitioners. As long as he stands at the helm, poetry is bound to survive another day. When it does die, let’s hope he’s here to write its elegy.

Eric Bies is the founding editor of Orange County Review of Books. His essays and reviews have appeared in World Literature Today, Asymptote, and American Book Review, among others.