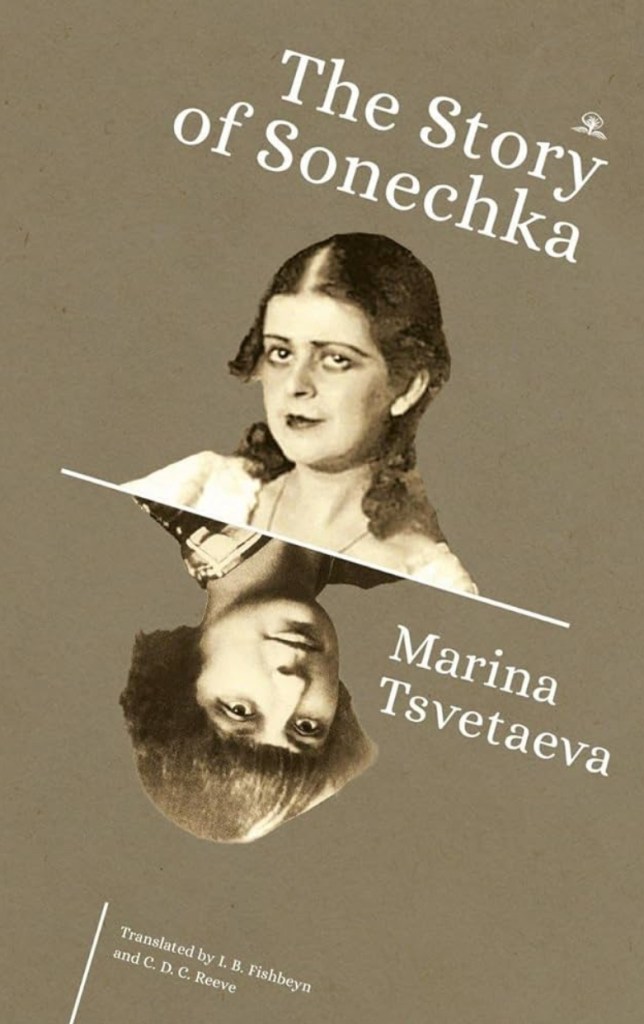

By Marina Tsvetaeva

Translated by I. B. Fishbeyn and C. D. C. Reeve

Cherry Orchard Books. 2025.

Reviewed by Eric Byrd

In November 1917 Marina Tsvetaeva and her husband Sergei departed Moscow for Koktebel in the Crimea. They reached the “gray-haired sea” in a “mad snow storm” and found their host Maximilian Voloshin “with a volume of Taine on his knees, frying onions.”

And while the onions are frying, reading aloud to S. and me, the destinies of Russia tomorrow and beyond.

“And now, Seriozha, there will be such and such … Remember.”

And softly, carefully, almost rejoicing, he shows us picture after picture. Like a magician revealing his secrets to children, he relates the course of the entire Russian Revolution five years in advance: the terror, the Civil War, the executions, the military outposts, the Vendée, the atrocities, the loss of godliness, the unloosed spirits of the elements, blood, blood, blood …

Voloshin’s kitchen prophecy (in Tsvetaeva’s diaristic Earthly Signs) nicely illustrates Simon Karlinsky’s remark that many Russian poets turned to “the precedent of Jacobin terror during the French Revolution to explain and elucidate the period of War Communism [1918-21].” With one or another volume of Les Origines de la France Contemporaine presumably still in his lap, Voloshin wrote The Deaf-Mute Demons (1919) and Verses on Terror (1923); while Tsvetaeva, with a cold and hungry Moscow before her eyes, and the memoirs of Casanova, the Duc de Lauzun and the Prince de Ligne on her mind, produced a cycle of verse dramas with French revolutionary settings.

Tsvetaeva wrote An Adventure, The Phoenix, and Fortuna in 1918-19, for Third Studio, an experimental adjunct of the Moscow Art Theater into whose company she was introduced by a chance encounter on the train to Koktebel: “above my head, on the top bunk” she heard a soldier recite a striking poem whose lines included:

And here is is, the dream of the grandfathers,

Who drank cognac and had the great discuss,

In Girondins’ cloaks, through snow and troubles,

With downcast bayonets burst in on us.

She asked the author’s name and on her return to Moscow sought out Pavel Antokolsky, a poet and actor whose colleagues at Third Studio included Sophia Holliday, called “Sonechka.” Tsvetaeva wrote Sonechka into all three of her eighteenth-century dramas (in Fortuna she played the porter’s daughter who comforts Lauzun while he awaits execution), and she became “the object of Tsvetaeva’s most intense Sapphic passion since her breakup with Sophia Parnok” (Karlinsky), “the female being,” Tsveteva told a friend years later, “whom I loved more than anyone else in the world. Perhaps more than all beings, male or female.” The Story of Sonechka is a novella-length memoir Tsvetaeva wrote in 1937. It is an especially dialogic-dramatic instance of her inimitable prose, and it has just this year appeared in English for the first time. Together with Kemball’s edition of The Demesne of the Swans, Gambrell’s of Earthly Signs, and Maya Chhabra’s translation of Fortuna (in Cardinal Points, Brown University’s Slavic Studies journal, volume 8), Sonechka brings Russianless readers very close to Tsvetaeva in a pivotal season of creation and witness.

As an actress Sonecka was a special case – her emotional range was limited, and physically she was too small for leading ladies – but her air of “ancient, century-old, eighteenth-century maidenhood” appealed to Alexei Stakhovich, a former Guardsman and Imperial aide-de-camp who had left court for the other stage. Tsvetaeva says his eyelids were of “the heavy breed that rarely open wide. Eyelids that are naturally haughty.” (In a flash I picture Evgeny Mravinsky.) With the cache of courtliness left by his old life Stakhovich was arbiter elegantarum, a tutor in etiquette and deportment to the youthful players. And he often called on Sonechka to demonstrate how a lady wears her hair, corrects a fallen stocking, bows, gives a hand, and moves gracefully even in the monstrous boots of midwinter Moscow: “Whatever one is wearing, there’s still the stride. Look at Sophia Evgeneva. Who could tell that on each of her little feet is a ton of iron, like on the prisoner Bonivard?”

After Stakhovich’s suicide in spring 1919 Tsvetaeva wrote a pair of poems in salute of his “complex lyrico-cynical-stoical-epicurian essence,” one of “the eighteenth century and youth.” The poem she brought to his burial but was forbidden to read reads in part:

The old world was on fire – fated.

– Nobleman, give way – to Woodcutter!

The mob was blooming, but around you

The air of the eighteenth century breathed.And the mob de-roofed the castles,

Straining for the desired loot –

“Bon ton, maintien, tenue,” you taught the boys –

To the accompaniment – of a crashing Universe.

And in one of those grand cries of anticontemporaneity that I so love in her, Tsvetaeva accosts Stakhovich’s ghost and demands to know why he didn’t fall in love “with my Sonechka” and take her away to live, one imagines, dans une folie à l’extrȇme pointe du Moscu romantique, to garble Sainte-Beuve:

You saw around her the air of the eighteenth century. What was missing, that you could not live through that horrid March day? What couldn’t you handle – one more hour without?

And she was nearby – alive, delightful, ready to love and to die for you – and dying without love.

Maybe you thought: she has her own young admirers … Yes, I saw ones like that! And so did – you.

How could you leave her to – all, each, any of those boys you were so fruitlessly teaching “bon ton, maintien, tenue”?

Later in 1919 Sonechka went off with a provincial troupe, married, and died of cancer in 1934. Tsvetaeva didn’t need to name Talleyrand to summon his remark that one had to have lived before 1789 to know the sweetness of life, douceur de vivre:

Sugar – is not a necessity, one can live without it, and for four years of the Revolution we did live without it, some substituting – treacle – for it, some – shredded beets, some – saccharine, some – nothing at all. Drinking unsweetened tea. No one dies of its absence. But they don’t live, either … A whole, live, white, piece of sugar – that’s what Sonechka was to me.

Eric Byrd is a librarian and archivist living in Minneapolis-St Paul, Minnesota.