The first thing anyone needs to know about a figure like Henry Darger, the Chicago janitor who spent decades privately composing and illustrating a fifteen-thousand-page epic titled In the Realms of the Unreal, is that he existed. Virtually unknown in life, Darger became famous in death – famous in the same romantic manner all outside artists tend to make it: as visionaries uncorrupted by the poisons of commerce and public opinion.

The same – similar – could be said of American artist Michael McMillan. Apart from a handful of appearances in the underground comics of the sixties and seventies; apart from an association with the likes of R. Crumb and Art Spiegelman; apart from the fact that he is, well, still living, McMillan, who was born in 1933, has largely avoided the limelight. Call it art for art’s sake: he’s done it for himself all along.

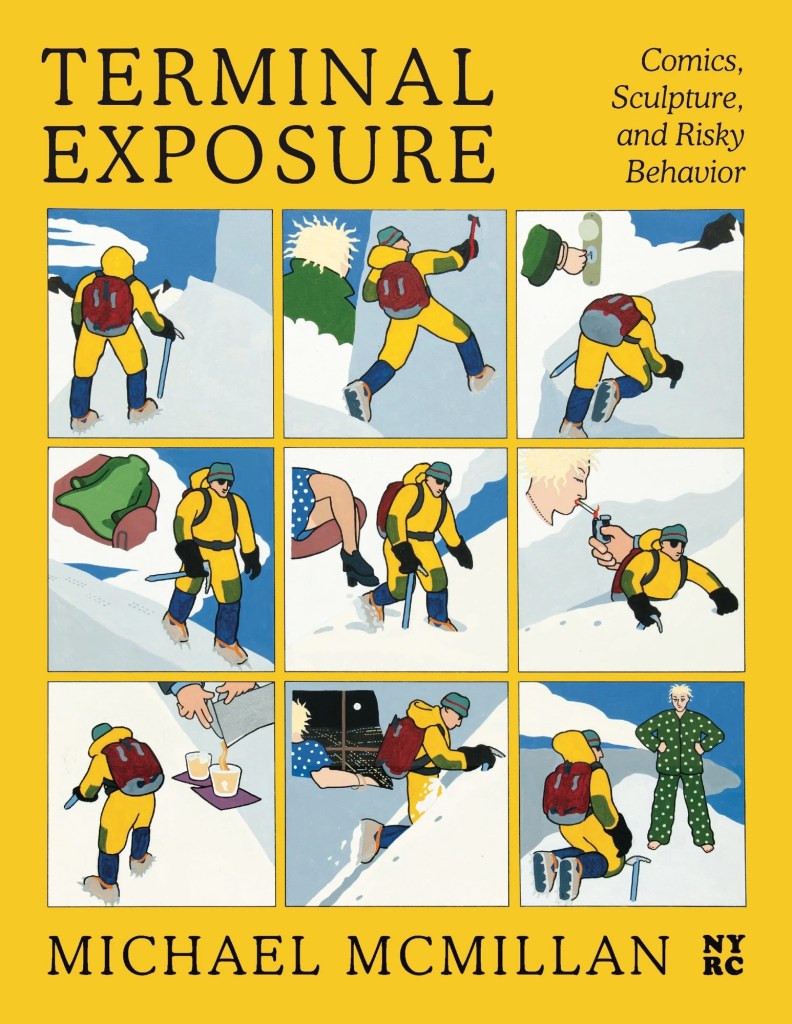

All of which makes the publication of Terminal Exposure, the first-ever collected edition of McMillan’s work, just the kind of moment for celebration no one ever sees coming. Spanning a career that kicked off in earnest in the 1960s, much of what’s collected here has never appeared elsewhere. While a long and quiet career in comics and cartooning fill out the bulk of the book, McMillan has also thrown in several pages dedicated to his work as a sculptor, a photographer, and a chronic, inveterate diarist.

This delightfully miscellaneous book opens with a six-page comics memoir (“Oakland California 1937. My father and I went for a thirty minute ‘aeroplane’ ride.”) tracing McMillan’s beginnings from a California suburb (“1938. The year of the pedal-car tractor.”) through adolescence (“1949. I began training at a time when running on roads was as common as walking on water.”), from one awakening (“Gave up religion, began reading books, and perceived my culture as a big scale con game.”) to the next (“Cosmic dialogue 1953: ‘School! Job! Car! Marriage! House! Kids! … Predictable boredom!!’”). His captioning is consistently supple, his narrative sense as sure as the ticking of a clock. Compositionally, the comics read effortlessly: here as elsewhere, full, balanced, uncluttered panels encourage you to linger without overwhelming your eye.

Next is a four-photo series documenting an odd act of public display: McMillan, downtown, standing beside a pair of long, triangular, winglike pieces of wood; McMillan strapping the pieces to his ankles; McMillan struggling to navigate the sidewalk. The caption reads: “Sculpture as a body extension. No symbolism intended. Think of Abe Lincoln’s stovepipe hat. What’s that all about?”

The sculptural work offers similar excursions into surreality. There are wooden busts of the characters that appear in the comics (supplying color, such as a green nose, to what’s largely black and white). There are crowds of bendy bodies – walkers – who pass each other as though navigating their own crowded sidewalk. Their armlessness and headlessness will remind you of Rodin, but the simple fact of their standing forth, frozen in motion, might be all these statues “mean”: No symbolism intended.

The third part of the book’s subtitle – Comics, Sculpture, and Risky Behavior – gives a nod to McMillan’s other, persistent passion: the great outdoors, mountaineering in particular. It’s difficult to imagine the nonagenerian scaling anything too steep these days, so it’s a joy experiencing the trails, boulders, inclines, and summits at second hand. Such adventurousness, not merely the free soloist’s suicidal daring, operates as a kind of unifying theme throughout the book. Like Gary Snyder if he could draw, McMillan’s artistry conveys an implicit philosophy of openness – to experience, nature, new ideas – that is equally refreshing and heartening.

Eric Bies is the founding editor of Orange County Review of Books. His essays and reviews have appeared in World Literature Today, Asymptote, Open Letters Review, Rain Taxi, and Full Stop, among others.