By Vincenzo Latronico

Translated by Sophie Hughes

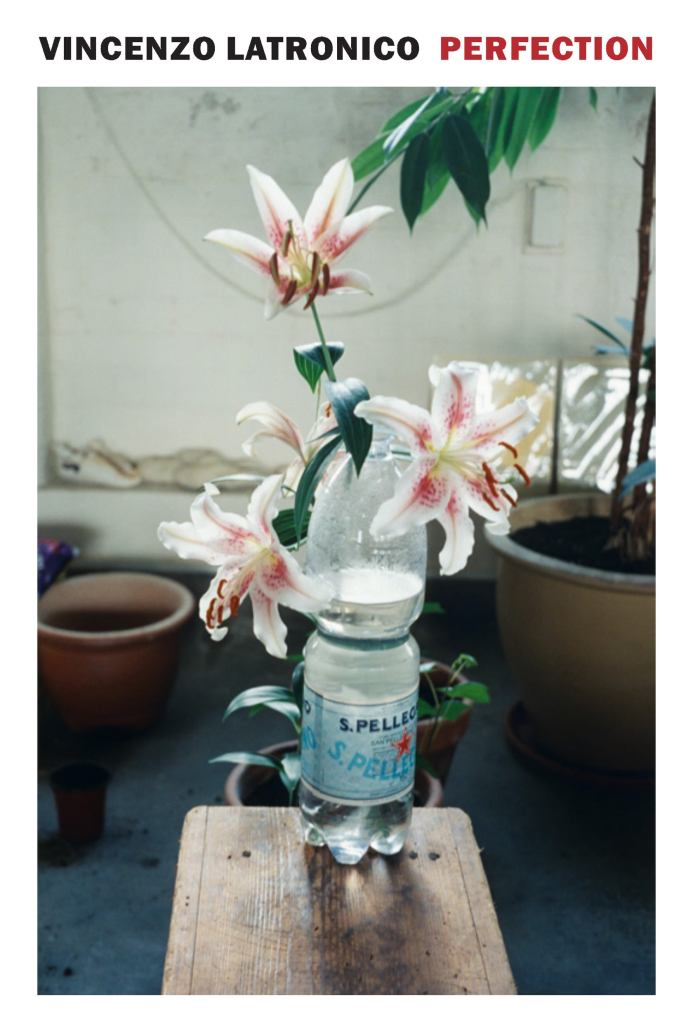

New York Review Books. 2025.

Reviewed by Eric Bies

Vincenzo Latronico is a different kind of novelist. Scientific, sociological, objective – he doesn’t pull any punches in his latest novel, Perfection, but neither will this review: the truth is that Latronico’s new book is less a novel than an ethnography, a somewhat tiresome case study in millennial ennui, a snapshot of a place in time sufficiently distant to prevail upon its author’s evident instinct for anthropology.

Perfection documents the lives of two young Italian transplants, Anna and Tom, in Obama-era Berlin. Hip to the latest in tech, ostentatiously left-leaning, culturally inclined in general, they’re the kind of people who go around calling themselves “creatives” – and, well, they are: they make a pretty good living as graphic designers, working from home before working from home was fashionable (before working from home was “WFH”!). And if any of this sounds familiar, that’s because it probably is: this shouldn’t be the first time you’ve heard their story. It’s the story, after all, of an entire generation of young people privileged to chart their own destinies but doomed to ruminate over the consequences of their historically unprecedented freedom of choice.

Properly speaking, their story is no story at all. Anna and Tom do all kinds of stuff and go to all kinds of places in the course of the book, but neither the one nor the other ever adds up to anything. Essentially plotless, the book moves in anti-climactic loops, and goes nowhere. Some pages rise to the occasion of depicting a half-realized scene, as when Anna and Tom spend an evening exploring a sex club, but most of the time the book reads with all the effortless, surface-level interest of a social-media scroll: Watch them as they navigate the city’s legendary tangle of bureaucratic red tape. Watch them as they design web pages for clients. Watch them as they hop bars, quaff craft beers, and have bad sex.

That all might sound dreadfully dull, and much of it is, but Latronico’s eye for detail is seriously penetrating. His ultra-perceptive sense for life as it was lived five, ten, even fifteen years ago might have made this book a memoir for the ages (it isn’t hard to imagine how he arrived at such an abundance of insight: this must be, more or less, the life he lived), and though virtually every page vibrates with recognition, Latronico consistently undercuts his own best efforts through a series of poor narrative decisions. He fails, for instance, to afford his characters a single line of dialogue: no one says a word in these pages – and that would be fine if the characters came alive by other means. But he also largely refuses to distinguish between Anna and Tom, forfeiting “he” and “she” for “they,” their identities, desires, and fears conflated in a droning ooze of sameness. The result is a book with rounded corners. Its verbal precision gives the appearance of daring, but even the pleasures of a sharply barbed and well-formed statement can’t cover for a lack of stakes.

Unable to make you care about his characters (one can scarcely muster the effort to hate them), Latronico does the next best thing, unloading one meticulously phrased sentence after another, the book chockablock with page-long descriptions of spaces and the things that fill them: Anna and Tom in their apartment, Anna and Tom at a warehouse party, Anna and Tom at the latest gallery opening. At his best, Latronico invokes the omniscient sweep of Georges Perec, who presides as a kind of patron saint over the book’s endless stockkeeping. Most of the time, though, he ends up sounding like an unrestrained realtor. In the book’s opening sequence, Anna and Tom’s Berlin apartment is described in exacting detail:

Sunlight floods the room from the bay window, reflects off the wide, honey-coloured floorboards and casts an emerald glow over the perforate leaves of a monstera shaped like a cloud. Its stems brush the back of a Scandinavian armchair, an open magazine left face-down on the seat. The red of that magazine cover, the plant’s brilliant green, the petrol blue of the upholstery and the pale ochre floor stand out against the white walls, their chalky tone picked up again in the pale rug that just creeps into the frame.

It’s an image of perfection. Or so you might think. Nostalgia, longing, restlessness, and discontent are always waiting in the wings. The book is quick to shift registers; Latronico is ready to pounce at the turn of a page. His book styles itself as an exceptionally dry satire but it ultimately succumbs to the same devices it seeks to skewer.

Eric Bies is the founding editor of Orange County Review of Books. His essays and reviews have appeared in World Literature Today, Asymptote, Open Letters Review, Rain Taxi, and Full Stop, among others.