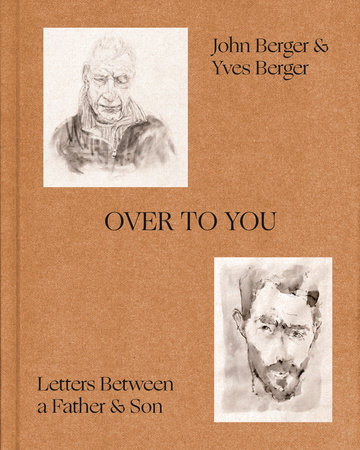

Over to You: Letters Between a Father and Son

By John Berger and Yves Berger

Pantheon. 2024.

Reviewed by Eric Bies

Of the three books he published in 1972 – the year John Berger became John Berger – the first, a collection of essays, is largely forgotten. The second, Ways of Seeing, became a bestseller. The third, a novel titled G., did not, but it won him the lasting prestige of a Booker Prize.

In 1976, Berger’s third wife, Beverly, gave birth to a son. They named him Yves. Unlike his father, who gave up painting to pursue writing, Yves went on to do both, and remains at them to do this day. His latest book, Over to You: Letters Between a Father and Son, is both a collaboration and a kind of retrospective: John Berger died in 2017.

The book makes an immediate impression of generosity: its eloquent design, the quality of its paper, the quantity of full-color illustrations (from drawings and paintings by the Bergers to the works of Van Gogh, Manet, Giacometti, Poussin, Twombly, and more) make a persuasive argument for the production of beautiful books in an age of increasingly digital texts.

The letters themselves, transcripts of handwritten ones composed between 2015 and 2016, capture a compelling slice of the last years of Berger’s life, and offer the enduring interest of a double portrait: first, of one of the greatest art critics of the twentieth century; second, of a father on equal footing with his son.

Readers will be forgiven for expecting Berger’s letters to match the intensity of his earlier works. (They don’t.) The remarkable quality of his attention – sufficiently sustained in these pages as to distinguish, on one occasion, one white rose from a garden of competing profusions – remains intact. But his touch is lighter, more tentative, his observations typically running to half the length of his son’s.

Readers will also be forgiven for projecting even the slightest semblance of strain or struggle onto the Bergers’ relationship. Across their span of letters there isn’t an inkling of resentment or envy, not a drop of that painful longing of a son to be free of his marvelously famous father’s shadow. Instead, a mutual passion for the arts sends both men in tireless pursuit of visual material to tip into their envelopes. They can’t help but reciprocate: to enthuse, to inspire, to admire. When Yves sends a picture of Max Beckmann’s (“a woman wearing a carnival mask. A cigarette in one hand, a clown hat in the other”), his father responds in kind:

A few days before I got your Beckmann, I received a postcard from Arturo [Di Stefano]. Here it is. I put Durer’s Screech Owl beside Beckmann’s Columbine, and together they make me smile. Their two faces and tummies wink at each other.

They tend to occupy complementary roles: the father as the wise, old sage, his son the restless philosopher. Here’s Yves charting a territory:

So much exceeds our understanding. So much remains open in what seems, or even is, closed. This gap between our consciousness and our feelings, between the visible and the invisible, between the said and the unsaid, leads to a kind of vertigo. A vertigo that’s not far from praying, or from madness. That’s the zone I would like us to meet. Are you coming?

His father responds with a “photo of a plant by Jitka Hanzlová – the Czech photographer of forests and horses,” and a painting by Caravaggio of Saint Paul thrown from his horse – “because it depicts exactly that moment of prayer or vertigo.”

Their spirited back-and-forth persistently navigates such wide-ranging terrain. The book offers a glimpse into the nature of their relationship, in which they trade memories, political sentiments, creative expressions, ontological investigations, and a profound love for one another. As brief as it is, it’s a thrill to watch it all unfold.

Eric Bies is the founding editor of Orange County Review of Books. His essays and reviews have appeared in World Literature Today, Asymptote, Open Letters Review, Rain Taxi, and Full Stop, among others.